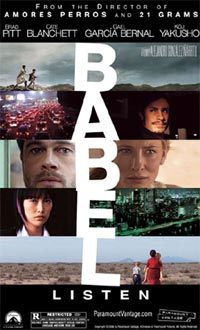

Babel (2006, Dir. Alejandro González Iñárritu):

Babel (2006, Dir. Alejandro González Iñárritu):

Come, let us go down, and there confuse their language, that they may not understand one another’s speech. So the Lord scattered them abroad from there over the face of all the earth, and they left off building the city.

— Genesis 11:7-8

We’re often looking for the Next Big Thing, and that Next Big Thing has an extra kick if it comes from outside our hermetically sealed universes. In the cannibalistic film industry, this holds doubly true — for all the reliance on tested formulas and rehashes of the latest hit novel/comic/TV show, Hollywood often lets its guard slip just long enough to allow a true innovator, auteur or garden-variety acclaimed filmmaker from abroad into its grasp. Think Hitchcock. Think Wilder. Think Ang Lee. In the best-case scenario, this cross-cultural pollination results in a heady mix of familiarility and originality; in the worst, it reeks of pandering and opportunism.

Which brings us to the interesting case of Alejandro González Iñárritu — interesting because even though he hails from Mexico and thus could be labeled “international,” his style of filmmaking seems ready-made for American arthouse acceptance. His breakthrough film, Amores Perros, played like an Altman movie shot through (or up?) with Tarantino sensationalism, and his first American film, 21 Grams, was a logical extension of that aesthetic. It’s easy to see why the film cognoscenti (and big-name stars like Sean Penn) flock to him — he tackles the Big Ideas (human loneliness, the randomness of tragedy) with a driving intensity that approximates integrity, he provides his actors with opportunities to chew the scenery, and he throws in some postmodern shufflings of time and narrative to stay hip. A litany of tragic accidents, mournful gazes, and dizzying jumps between now, then, and the future, his films are undeniably bracing, but jaw-clenchingly grim (the only humor to be found is of the unintentional kind, as in Are we really supposed to believe Sean Penn as a tortured math professor?). For those of us who haven’t lost our masochistic Puritan streaks, Iñárritu’s work allows us to feel ennobled by our collective misery, and it doesn’t hurt if we get to see Sean Penn and Naomi Watts make out while we’re at it.

Iñárritu’s new film Babel is the latest chapter in his life-is-a-shambles view of the world, and yet it is something more, as well. The narrative trickery has been cut to a minimum: the storytelling gets topsy-tervy at a few points, but this time the whiplash is mainly of the geographic variety, as we are ping-ponged from Morocco to Japan to southern California and Mexico. The plot, written by Iñárritu’s collaborator Guillermo Arriaga and based on an idea by the director, follows the fortunes (mostly disastrous) of a selection of people whose lives are tenuously connected by an accidental shooting. At the outset, the mischievous sons of a Moroccan goat herder (Said Tarchani and Boubker Ait El Caid) get hold of their father’s rifle, and in a competition for bragging rights, they take pot shots at a passing tourist bus in the mountains. One of the bullets pierces Susan (Cate Blanchett), the disaffected wife of Richard (Brad Pitt), and while the two of them are stranded in an isolated village, the seconds ticking away on Susan’s life, their Mexican nanny Amelia (Adriana Barraza, never less than convincing) faces her own conundrum — stay with Richard and Susan’s kids (Elle Fanning and Nathan Gamble) as Richard requested, or hightail it to Mexico for a day to witness the all-important marriage of her son? Meanwhile, in Japan, deaf-mute high school girl Chieko (Rinko Kikuchi), frustrated with her isolation from the world and her recently widowed father (Kôji Yakusho of Shall We Dance? fame), craves contact and a little bit of lovin’, and isn’t above resorting to extreme measures. Shake and stir all the above, throw in further devilish coincidences, connections, and happenstances, and you can already imagine the arthouse denizens salivating: How international! How bold! How challenging!

Iñárritu’s new film Babel is the latest chapter in his life-is-a-shambles view of the world, and yet it is something more, as well. The narrative trickery has been cut to a minimum: the storytelling gets topsy-tervy at a few points, but this time the whiplash is mainly of the geographic variety, as we are ping-ponged from Morocco to Japan to southern California and Mexico. The plot, written by Iñárritu’s collaborator Guillermo Arriaga and based on an idea by the director, follows the fortunes (mostly disastrous) of a selection of people whose lives are tenuously connected by an accidental shooting. At the outset, the mischievous sons of a Moroccan goat herder (Said Tarchani and Boubker Ait El Caid) get hold of their father’s rifle, and in a competition for bragging rights, they take pot shots at a passing tourist bus in the mountains. One of the bullets pierces Susan (Cate Blanchett), the disaffected wife of Richard (Brad Pitt), and while the two of them are stranded in an isolated village, the seconds ticking away on Susan’s life, their Mexican nanny Amelia (Adriana Barraza, never less than convincing) faces her own conundrum — stay with Richard and Susan’s kids (Elle Fanning and Nathan Gamble) as Richard requested, or hightail it to Mexico for a day to witness the all-important marriage of her son? Meanwhile, in Japan, deaf-mute high school girl Chieko (Rinko Kikuchi), frustrated with her isolation from the world and her recently widowed father (Kôji Yakusho of Shall We Dance? fame), craves contact and a little bit of lovin’, and isn’t above resorting to extreme measures. Shake and stir all the above, throw in further devilish coincidences, connections, and happenstances, and you can already imagine the arthouse denizens salivating: How international! How bold! How challenging!

With a title like Babel, the theme of misunderstanding would seem to be the lynchpin of the movie (or as James Brown puts it: “talkin’ loud and saying nothing”). Richard finds himself helpless at communicating not just with the locals but with the unsympathetic tourists on the bus who just want to get the hell out and leave him there; an international relations snafu sees the U.S. State Department treat Susan’s shooting as a “terrorist attack” (a potential jibe at all-about-us American paranoia that is never followed up on); and Chieko’s thirst for sex or something even more intimate, and her inability to express that desire, lead her to flash strangers in restaurants, or in the film’s most arresting sequence, make a pass at an earnest young cop by baring her entire body to him. However, Babel is less about what we don’t understand about each other than it is about how we’re all interconnected by the whims of ill fortune. Murphy’s Law isn’t just an abiding principle in this universe — it is the entire universe. When Amelia decides to drag Richard and Susan’s kids with her to Mexico for the day, is there any doubt that the enterprise will end badly? Likewise, as the local police net tightens around the two Moroccan boys, you can be sure that there will be another tragic death or two involved. In Babel, the object isn’t escape so much as survival.

Say this for Iñárritu — his instincts as a filmmaker are peerless. Visually, Babel is a stunner, and cinematographer Rodrigo Pietro wrings arresting images from the beauty and squalor.The film’s first major transition, from the parched desert of Morocco to the cozy suburban living room of Richard and Susan’s family, is a startling moment — with a simple cut between scenes, we are flung between geographic and cultural divides, and the juxtaposition is breathtaking. With the globe-spanning locales and sprawling narrative, Iñárritu knows he’s being ambitious, and he luxuriates in that fact. Whereas a typical American film working with this concept would settle for a few picture-postcard shots and a dash of ethnic music on the soundtrack, Iñárritu immerses us in each of the film’s wildly disparate environments. Having seen my share of Middle Eastern films over the years, it’s impressive how Iñárritu manages to mirror their textures, rhythms, and tone in the Moroccan passages. Likewise, his dead-on evocations of Tokyo night life are balanced by a winsome naturalism that is the calling card of Asian New Wave cinema (think Wong Kar Wai, if Wong had a soul as well as a heart and a brain). And when he hits his home turf of Mexico for a wedding party that is by turns wistful, boisterous, chaotic, romantic, and ever so slightly sinister, it’s clear that we’re in the presence of a major talent.

Say this for Iñárritu — his instincts as a filmmaker are peerless. Visually, Babel is a stunner, and cinematographer Rodrigo Pietro wrings arresting images from the beauty and squalor.The film’s first major transition, from the parched desert of Morocco to the cozy suburban living room of Richard and Susan’s family, is a startling moment — with a simple cut between scenes, we are flung between geographic and cultural divides, and the juxtaposition is breathtaking. With the globe-spanning locales and sprawling narrative, Iñárritu knows he’s being ambitious, and he luxuriates in that fact. Whereas a typical American film working with this concept would settle for a few picture-postcard shots and a dash of ethnic music on the soundtrack, Iñárritu immerses us in each of the film’s wildly disparate environments. Having seen my share of Middle Eastern films over the years, it’s impressive how Iñárritu manages to mirror their textures, rhythms, and tone in the Moroccan passages. Likewise, his dead-on evocations of Tokyo night life are balanced by a winsome naturalism that is the calling card of Asian New Wave cinema (think Wong Kar Wai, if Wong had a soul as well as a heart and a brain). And when he hits his home turf of Mexico for a wedding party that is by turns wistful, boisterous, chaotic, romantic, and ever so slightly sinister, it’s clear that we’re in the presence of a major talent.

But for all his elasticity as a filmmaker, Iñárritu doesn’t allow his characters to breathe outside the calamities he has arranged for them — ironic, given the notable actors like Blanchett who have all but begged to be in his films. Less flesh-and-blood beings than pinballs, the people in Babel take a back seat to plot, for the most part. Pitt, armed with facial wrinkles and salt-and-pepper hair, gets to squirm and bellow and express concern, and that’s about all we know about him. Likewise, Blanchett’s character can be summed up within her first few seconds of screentime, as she disastefully tosses away a glass of Coke served up by the locals (“You don’t know what kind of water is in there!”). And then there’s Amelia’s wild nephew Santiago (the estimable Gael García Bernal), who is a caricature of the Mexican hombre: he packs a pistol, drives around drunk, antagonizes and flees the U.S. border patrol, and eventually abandons Amelia and her charges in the California desert. His only function in the movie appears to be screwing up her life.

Babel works itself up to a fine pitch — it can’t avoid it, with all the escalating crises on hand. And yet, when all is resolved, one can’t help feeling let down by the muffled conclusions to each of its storylines. Richard and Susan’s tale, which is ostensibly the most critical from a life-and-death perspective, sputters when it should tighten up, and we are meant to feel moral outrage at Amelia’s plight (those damn immigration police!), but like the U.S. State Department and the “terrorist act,” the political commentary is left dangling without a punchline. Still, two performances rise above the murk. Given an essentially unbelievable character (no one in their right mind would do the things she does and expect to get off scot-free), Barraza somehow manages to maintain her dignity and our sympathy as Amelia. Even as the script contrives to place her in the squirmiest situation possible, her cries for help in the middle of the desert, with her red wedding clothes in tatters and her makeup running down her face, are indelible.

Babel works itself up to a fine pitch — it can’t avoid it, with all the escalating crises on hand. And yet, when all is resolved, one can’t help feeling let down by the muffled conclusions to each of its storylines. Richard and Susan’s tale, which is ostensibly the most critical from a life-and-death perspective, sputters when it should tighten up, and we are meant to feel moral outrage at Amelia’s plight (those damn immigration police!), but like the U.S. State Department and the “terrorist act,” the political commentary is left dangling without a punchline. Still, two performances rise above the murk. Given an essentially unbelievable character (no one in their right mind would do the things she does and expect to get off scot-free), Barraza somehow manages to maintain her dignity and our sympathy as Amelia. Even as the script contrives to place her in the squirmiest situation possible, her cries for help in the middle of the desert, with her red wedding clothes in tatters and her makeup running down her face, are indelible.

Then there is Kikuchi as Chieko: happily, the story is much kinder to her, and it is in the Tokyo segments that Babel really soars. In notable opposition to the movie’s other passages, no lives are at stake, nobody’s fate is dangling at the whim of an angry god, and yet by simply following the rhythms of Chieko’s daily life, her run-ins with would-be lovers, night clubs, and playground swings, Iñárritu documents a yearning for connection that has an urgency and poignancy that the other storylines, with their sturm and drang, can barely muster. Whether she’s flipping her skirt at a gawking passerby, grooving soundlessly to an Earth, Wind and Fire remix, giving a school official the middle finger, or breaking down as she throws her naked body into the arms of her father, Kikuchi is unstoppable; her spontaneity is the spark that provides the film with its only whiff of true mystery. Fittingly enough, Babel ends with her and her father standing alone yet together on the balcony of her apartment building at night, the camera pulling back to reveal the manifold twinkling lights of Tokyo, thousands of inhabitants in their own private worlds. For all its beautiful desolation, the sight is a comforting one, for it suggests that if Iñárritu can get past his stifling obsessions with tragedy and human folly, he’ll graduate from international arthouse darling to pretty damn devastating director.

Then there is Kikuchi as Chieko: happily, the story is much kinder to her, and it is in the Tokyo segments that Babel really soars. In notable opposition to the movie’s other passages, no lives are at stake, nobody’s fate is dangling at the whim of an angry god, and yet by simply following the rhythms of Chieko’s daily life, her run-ins with would-be lovers, night clubs, and playground swings, Iñárritu documents a yearning for connection that has an urgency and poignancy that the other storylines, with their sturm and drang, can barely muster. Whether she’s flipping her skirt at a gawking passerby, grooving soundlessly to an Earth, Wind and Fire remix, giving a school official the middle finger, or breaking down as she throws her naked body into the arms of her father, Kikuchi is unstoppable; her spontaneity is the spark that provides the film with its only whiff of true mystery. Fittingly enough, Babel ends with her and her father standing alone yet together on the balcony of her apartment building at night, the camera pulling back to reveal the manifold twinkling lights of Tokyo, thousands of inhabitants in their own private worlds. For all its beautiful desolation, the sight is a comforting one, for it suggests that if Iñárritu can get past his stifling obsessions with tragedy and human folly, he’ll graduate from international arthouse darling to pretty damn devastating director.