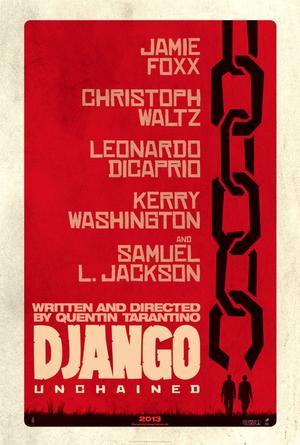

Django Unchained (2012, Dir. Quentin Tarantino):

Django Unchained (2012, Dir. Quentin Tarantino):

Like all the great auteurs he studied when he was a video store clerk, Quentin Tarantino wants to control his own narrative. As movie-making becomes an ever more cannibalized experience, with every event film cribbing its moves from a previous film, Tarantino may be the master cannibal of them all, freely borrowing (and associating) from every influence in his video library, each of his pictures part of a larger meta-commentary on genre. Want some kung fu? Go Kill Bill. How about a heist movie? Reservoir Dogs. Grindhouse? Grindhouse, of course. (Where Four Rooms fits in is anyone’s guess, and apparently Tarantino agrees, given his refusal to acknowledge the film’s existence.) It’s no longer about just making movies; it’s about adding another chapter to an ongoing treatise in which professor Tarantino expounds on the forms of potboiler cinema, all rendered with a post-modern spin and a sincere tip of the cap.

So here we are with Tarantino’s latest greatest hits tribute, Django Unchained (before you ask, no, it has next to nothing in common with the sixties Western Django), the second in what he is already framing as a “history” trilogy after the Nazi-hunting Inglorious Basterds. This time we’re in the pre-Civil War South, slavers are the bad guys, and our heroes are bounty hunters seeking a fistful of dollars. Yes, Django is embracing the spaghetti western aesthetic that Kill Bill, Vol. 2 hinted at, and from the old-school Columbia logo that opens the picture to the ’70s-style font for the titles, including a credit for “Don Johnson as Big Daddy,” an attribution which can’t help but draw a titter, we know we’re safely in the exploitation zone.

Well, not quite. While it’s true that as per usual, we don’t go five minutes without a reference to a great Western (the original Django, Franco Nero, shows up for a fun but meaningless cameo, and Ennio Morricone should pick up some nice royalties on the soundtrack — two mules for Sister Sara, anyone?), there’s also a sense that Tarantino is aiming at something above a genre exercise, especially when it concerns the titular hero (Jamie Foxx), a slave freed by bounty hunter Dr. King Schultz (Christoph Waltz). While at first Django is just a temporary necessity for Schultz (his help is required to identify a family of killers Schultz is seeking), he proves to have a taste for the bounty business himself, and when he reveals that his ultimate aim is to save his wife Broomhilda (Kerry Washington) from the clutches of dastardly plantation owner Calvin Candie (Leonardo DiCaprio), the film acquires a moral imperative that Tarantino treats with the utmost seriousness.

In its first act, Django is as matter-of-fact as anything Tarantino has done since Jackie Brown (1997), with the redoubtable Robert Richardson filming in static medium shots, punctuated by a few slo-mo scenes of carnage. Mostly though, our attention is held by the emerging chemistry between the two leads. As Schultz, Waltz is chatty and genial — armed with a broad vocabulary and precise diction, he’s a snake that mesmerizes with words before striking — and yet like many spaghetti western heroes, he has a hidden conscience; when he is exposed to slavery’s true horrors and averts his eyes, he gains something resembling three dimensions. Foxx has the more difficult part, as Django is really a sketch of a character, and more of a wish-fulfillment fantasy than anything else, but he turns in a cagey performance, whispery and recessive early on, gaining in strength as the story progresses.

In its first act, Django is as matter-of-fact as anything Tarantino has done since Jackie Brown (1997), with the redoubtable Robert Richardson filming in static medium shots, punctuated by a few slo-mo scenes of carnage. Mostly though, our attention is held by the emerging chemistry between the two leads. As Schultz, Waltz is chatty and genial — armed with a broad vocabulary and precise diction, he’s a snake that mesmerizes with words before striking — and yet like many spaghetti western heroes, he has a hidden conscience; when he is exposed to slavery’s true horrors and averts his eyes, he gains something resembling three dimensions. Foxx has the more difficult part, as Django is really a sketch of a character, and more of a wish-fulfillment fantasy than anything else, but he turns in a cagey performance, whispery and recessive early on, gaining in strength as the story progresses.

The two men’s initial adventures have a picaresque quality, including a throwdown with a decrepit sheriff who happens to be a wanted criminal, and a near-surreal encounter with Don Johnson’s Big Daddy (a nasty plantation owner, natch), who also happens to belong to the local chapter of the KKK, leading to a comical night-time assault that is the funniest passage in the film (“Let’s go no bags this time,” one character suggests when the group’s Klan hoods prove faulty). Most of the humor is anachronistic, as when Schultz notes Django’s proficiency with a rifle: “The kid’s a natural,” he marvels, as if sizing up a major-league pitching prospect. We even get some sly shifts in moral complicity between our characters, as Django becomes accustomed with the idea of killing a man in cold blood, while Schultz gains a sense of something larger than just earning money.

Of course, this is a Tarantino film, and irreverence is part of the deal. When Schultz and Django go undercover to save Broomhilda, the experienced hunter advising the freed slave, “Don’t break character,” we know damn well that Tarantino will gleefully disregard his own advice, subtlety giving way to Grand Guignol. Sure enough, we soon have the very modern sounds of James Brown and 2Pac accompanying our duo on their quest, the camera goes all whip-zoomy at key moments, and the almost genteel violence of the film’s first half is erased by an eruption of splatter and gore in the second (the climactic gun fights must set a record in exploding squibs and sheer gallons of blood caking the pastel walls of Candie’s mansion). And it wouldn’t be a complete Tarantino experience if we didn’t get the pleasure of seeing male genitalia battered, mangled, or shot off — in lieu of true grit, Freudian nastiness will have to do. It’s all bracing if not necessarily cathartic, with Foxx and Waltz strangely subsidiary for much of the film’s second half. Such confused syntax is part of the sloppiness, or part of the fun, depending on your point of view; at least like every good showman, Tarantino provides some pretty fireworks.

Of course, this is a Tarantino film, and irreverence is part of the deal. When Schultz and Django go undercover to save Broomhilda, the experienced hunter advising the freed slave, “Don’t break character,” we know damn well that Tarantino will gleefully disregard his own advice, subtlety giving way to Grand Guignol. Sure enough, we soon have the very modern sounds of James Brown and 2Pac accompanying our duo on their quest, the camera goes all whip-zoomy at key moments, and the almost genteel violence of the film’s first half is erased by an eruption of splatter and gore in the second (the climactic gun fights must set a record in exploding squibs and sheer gallons of blood caking the pastel walls of Candie’s mansion). And it wouldn’t be a complete Tarantino experience if we didn’t get the pleasure of seeing male genitalia battered, mangled, or shot off — in lieu of true grit, Freudian nastiness will have to do. It’s all bracing if not necessarily cathartic, with Foxx and Waltz strangely subsidiary for much of the film’s second half. Such confused syntax is part of the sloppiness, or part of the fun, depending on your point of view; at least like every good showman, Tarantino provides some pretty fireworks.

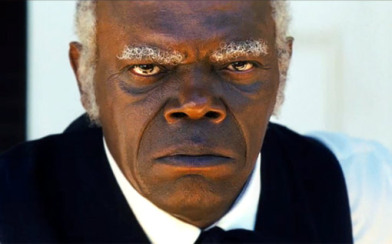

Whatever juice Django has down the stretch comes from DiCaprio and Samuel L. Jackson as his right-hand houseboy Stephen, who in helping his master perpetuate his domination over his fellow slaves is the most despicable character in the film. Neither of them are completely convincing, but it’s entertaining to see DiCaprio ham it up in a role that doesn’t require him to carry the world on his shoulders for once, and while Jackson breaks into some jarring vernacular which wouldn’t be out of place on the mean streets of Pulp Fiction, he’s also more focused and in the moment than he has been in a while (strange that someone like Tarantino, often accused of being a “black wanna-be” given his overriding affection for blaxploitation flicks, tends to coax out Jackson’s best performances). By the time Django rides in for a final reckoning against Stephen, you’ll be happy to cheer him on as he blows a plantation (and by extension, slavery) to smithereens.

Whatever juice Django has down the stretch comes from DiCaprio and Samuel L. Jackson as his right-hand houseboy Stephen, who in helping his master perpetuate his domination over his fellow slaves is the most despicable character in the film. Neither of them are completely convincing, but it’s entertaining to see DiCaprio ham it up in a role that doesn’t require him to carry the world on his shoulders for once, and while Jackson breaks into some jarring vernacular which wouldn’t be out of place on the mean streets of Pulp Fiction, he’s also more focused and in the moment than he has been in a while (strange that someone like Tarantino, often accused of being a “black wanna-be” given his overriding affection for blaxploitation flicks, tends to coax out Jackson’s best performances). By the time Django rides in for a final reckoning against Stephen, you’ll be happy to cheer him on as he blows a plantation (and by extension, slavery) to smithereens.

Django and Inglorious Basterds are cut from the same cloth, both stressing character drama while whipping the audience into a fervor for the bad guys (Nazis, slavers) to get their just desserts. Inglorious, which has the courage of its gonzo convictions to go all the way and rewrite history (take that, Hitler!), remains the superior film — sure it appeals to all our base adolescent fantasies about war movies and men on a mission, but it also presents recognizably human dimensions in its heroes and villains, capped with a tribute to cinema that outdoes any of the sanctimony someone like Martin Scorcese might have brought to the table. For all its ruckus, bloodshed and human interest, at its heart Django is a simple tale about revenge being served cold. “Tell us a story about the circus,” a character pleads at one point, and Django is just that, a carnival of wonders and creeps, replete with a nice moral and Jamie Foxx trotting magnificently on his horse, as imposing a representation of negritude as we’ve seen in the cinema lately. Whether or not you approve of his methods, you have to hand it to Tarantino — he keeps his film history class energized. ■

2 comments