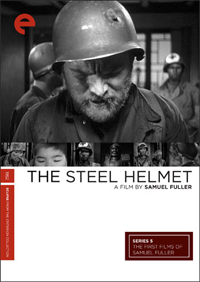

The Steel Helmet (1953, Dir. Samuel Fuller):

With North and South Korea trading threats once again nearly five decades after the Korean War, it’s a fitting time to remember Sam Fuller. World War II vet, two-fisted screenwriter and director, endlessly devoted to causes of social equality that naturally got him branded a Commie and gadfly, the pugnacious Fuller was of his time and beyond it, and his early B-grade Korean War drama The Steel Helmet, the film that launched his fame, amply illustrates that fact.

The very first image, a close-up of a motionless helmet sitting on a hilltop, has the succinct, near-poetic detail Fuller has become famous for, as the helmet, replete with fresh bullet hole, unexpectedly lurches forward. It belongs to Sgt. Zach (Dan Evans), sole survivor of a massacre, miraculously saved when the bullet intended for his brain instead rattled inside and out of his helmet. With clenched features and a perpetual cigar glued to his mouth, Zach is the archetypal super-competent soldier who doesn’t suffer fools or incompetent superiors gladly, and yet at the beginning of the film, his hands tied behind his back and slithering on the ground, he resembles nothing so much as a trussed pig. To his rescue comes an eager South Korean boy (William Chun) who Zach nicknames “Short Round” (this film must be in heavy rotation in Steven Spielberg’s film library — its influence shows up in everything from Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom to Saving Private Ryan), and together they stumble upon the ragtag remnants of other units, a veritable cross-section of U.S. society: by-the-book, educated Lieutenant Driscoll (Steve Brodie), Thompson, a put-upon black medic (James Edwards, prefiguring similar roles in The Killing and The Manchurian Candidate), “Conchie,” a former conscientious objector-turned-priest (Robert Hutton), a callow, prematurely bald radio operator (Robert Manahan) and Sgt. Tanaka (Richard Loo), who goes by the moniker “Buddha-head” and happens to be the only soldier apart from Zach who is useful in a pinch.

The very first image, a close-up of a motionless helmet sitting on a hilltop, has the succinct, near-poetic detail Fuller has become famous for, as the helmet, replete with fresh bullet hole, unexpectedly lurches forward. It belongs to Sgt. Zach (Dan Evans), sole survivor of a massacre, miraculously saved when the bullet intended for his brain instead rattled inside and out of his helmet. With clenched features and a perpetual cigar glued to his mouth, Zach is the archetypal super-competent soldier who doesn’t suffer fools or incompetent superiors gladly, and yet at the beginning of the film, his hands tied behind his back and slithering on the ground, he resembles nothing so much as a trussed pig. To his rescue comes an eager South Korean boy (William Chun) who Zach nicknames “Short Round” (this film must be in heavy rotation in Steven Spielberg’s film library — its influence shows up in everything from Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom to Saving Private Ryan), and together they stumble upon the ragtag remnants of other units, a veritable cross-section of U.S. society: by-the-book, educated Lieutenant Driscoll (Steve Brodie), Thompson, a put-upon black medic (James Edwards, prefiguring similar roles in The Killing and The Manchurian Candidate), “Conchie,” a former conscientious objector-turned-priest (Robert Hutton), a callow, prematurely bald radio operator (Robert Manahan) and Sgt. Tanaka (Richard Loo), who goes by the moniker “Buddha-head” and happens to be the only soldier apart from Zach who is useful in a pinch.

You can see where this is going, or at least you think you do: these very different men will learn the value of friendship and pitch in together against a common faceless enemy — the ultimate American melting pot embodied in countless war films past. Well, not quite. Fight these men do, and help each other in the end they will, but not because of any camaraderie or new-found respect, but because it’s either kill or be killed. Fuller has seen too much to rely on flag-waving or homilies. “Nothing like the infantry,” Zach quips. “You get hit and you’re dead or alive, but at least you’re on the ground.” When the squad comes upon a dead G.I., it’s the pragmatic cynic Zach who warns them against disturbing the corpse, and when a booby-trap planted on the body results in death, it’s Zach who openly sneers at his lieutenant: “What a fouled-up outfit I got myself into.” The violence in the film both confirms and belies that gallows-humor, matter-of-fact perspective, as when Zach and Buddha-head take out a tag team of snipers in an expertly edited and choreographed sequence — they may be just “making money,” as Zach puts it, but it’s clear these professionals take pride in what they do.

“Don’t let your emotions get the best of you. Dead man’s nothing but a corpse. Nobody cares who he is now.”

“Don’t let your emotions get the best of you. Dead man’s nothing but a corpse. Nobody cares who he is now.”

— Sgt. Zach, The Steel Helmet

Yet it becomes apparent that Zach is a melange of conflicting emotions — perhaps the bullet that grazed his head did some damage after all. He may be committed to staying alive, commanding officers or mission requirements be damned, but a tale of his D-Day experiences (“Let’s get off the beach and die inland”) suggests there are suicidal impulses in there, and while he openly shies from any kind of friendship, he and Short Round build a rough camaraderie that leads to devastating consequences. When the group holes up in a Buddhist temple and captures a runty North Korean major (Harold Fung), the film’s conscience is laid bare: while Zach is delighted that a POW will earn him a “furlough in Tokyo,” the major is intent on taunting and interrogating his captors, sowing seeds of rebellion. He points out to Tanaka that he and his brethren were shuttled off to internment camps during World War II (“They hate us because we have the same eyes”), and cajoles Thompson on his lack of rights back home (“You have to sit in the back of a public bus, isn’t that so?”). Pretty heady stuff for an early ’50s war film, and Fuller is unsentimental and un-showy in tackling the issues; he makes today’s filmmakers seem positively clunky in their approach to similar themes. The Steel Helmet‘s low budget is apparent (southern California and studio-bound sets subbing for North Korea), but Fuller’s spare, concise style dates the film better than most.

Film is like a battleground… Love, hate, action, violence, death. In one word, emotion!

Film is like a battleground… Love, hate, action, violence, death. In one word, emotion!

— Samuel Fuller, Pierrot le Fou

It should be noted that The Steel Helmet is no anti-war polemic — like many from the “Finest Generation,” Fuller was schooled and shaped by World War II, in which heroism and incongruity intermixed, and his very clear affection for the Army and macho bravery is shaded by his journalist’s eye for detail. Everything comes to a head in a final Alamo-like stand against a bevy of Korean troops that is as over-the-top, melodramatic and even impressionistic as you can get. Shellshocked, Zach stumbles into the frame like the ghost from a Kabuki play even as the imperious Buddhist statue that dominates the temple gazes on vacantly; cowed lieutenants and conscientious objectors alike pull themselves together in an orgiastic blaze of glory; and in a bracing twist, it is the misfits and unwanted soldiers who survive the conflagration. Here combat has clear sexual undertones, as stalwart soldier Zach is spent and satiated in victory — yet one look at his sagging shoulders and hooded eyes at film’s end tells a larger tale, as does the movie’s epitaph: “This story has no ending.” War movies even today hinge on stock heroism while making gestures at the fact that War is Hell — The Steel Helmet dances its own dance, suggesting that war is both Hell and Heaven, where the delirium of combat can be laughed at, feared, but also reveled in. Just like its director, it’s not pretty, it’s not even politically correct, but it has the unmistakable tang of truth.