|

Kekexili: Mountain Patrol (2004, Dir. Lu Chuan)

“Tibetans always point knives towards themselves.”

— Ritai, Kekexili: Mountain Patrol

Reviewing a mainland China film can be an interesting, if sometimes tortuous, exercise. Still a monolithic, forbidding nation in our eyes, China and its films are dissected by critics from every conceivable political angle: How did this work clear the official censors? What messages within can be interpreted as supporting the current regime? Or: Are there signs of resistance to the party line in this film? Where is the subversion? This can lead to enlightening commentary — see the early works of Zhang Yimou and Chen Kaige, which escaped censure by locating their narratives in long-ago China — or it can lead to shortsighted conclusions (see the hulabaloo about Zhang’s Hero, which many read as an endorsement of the current Communist leadership’s strong-arm tactics, while conveniently forgetting that tyranny has existed since time immemorial — sometimes an emperor is just an emperor).

In the case of Lu Chuan’s KeKexili: Mountain Patrol, which turned out to be the one film I saw at the Asian American Film Festival that has been guaranteed local U.S. distribution (through no less than National Geographic), the desire to dissect seems particularly apt. The story, based on true events, is a government public relations dream: In the early 90s, ruthless poachers slaughtered thousands of Tibetan antelope in the great northwestern plateau of Kekexili for their pelts. With the antelope on the verge of extinction, an under-funded and under-equipped band of locals formed a militia to thwart the interlopers. Their struggles brought to light by a young journalist from Beijing named Ga Yu (portrayed by Zhang Lei in the film), the government ultimately designated Kekexili as a wildlife preserve, bringing the antelope back from the brink — and they all lived happily ever after (well, not exactly, but in the self-congratulatory end titles slapped on at the close of this movie, it certainly feels that way).

If painting a picture of benevolent government helps China’s leaders sleep better at night, so be it — it’s certainly no worse than the typical song and dance any government trots out to placate the skeptical masses. But it stands in stark opposition to what the film is really about: nature and man (stress the “man”) under stress.

|

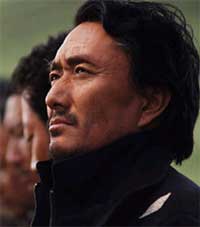

After a brutal opening sequence in which poachers slaughter a host of antelope and kill a patrolman, we are introduced to Ga Yu as he arrives in the area and meets militia captain Ritai (played with leathery authority by Duobuji). Initially suspicious of Ga and his desire to report on the troubles in the region to a national audience, Ritai has barely enough time to soften his attitude before he and his men bundle into two rickety jeeps with Ga in tow. Their mission: track down and arrest the bandits responsible for the patrolman’s death, even though they could be anywhere in the vast, three-mile-high tundra.

As that synopsis indicates, Kekexili is not the environmentalist polemic it has been pegged as, but a modern Western, and is interested in humans first and foremost. Save for the opening scene and a few mercifully brief shots of carcasses, the Tibetan antelope are nowhere to be seen. Instead, we become acquainted with the lives of these hardy locals, the way they dance and sing to keep their spirits up, the essential loneliness of their quest. Cinematographer Cao Yu, who had to brave extreme conditions to shoot the movie, deserves some kind of medal for his work, as the plateau stretches out empty and forbidding in all directions, like an alien moonscape. Within this stark setting, the posse is often framed as tiny figures, dwarfed by the elements. Here, a simple flat tire or unexpected storm can spell the difference between life and death, and as the calamities accumulate, the quest grows more protracted and desperate, the rations and gas run low, and the men are forced to violate their principles and even sell antelope pelts to continue the journey, the tale becomes one of outright survival, in which considerations of catching bandits and doing the right thing are afterthoughts.

|

Through it all, Ritai remains obsessed with the mission, even as his men’s numbers dwindle (the quotation that opens this essay is telling proof of his self-destructive stubbornness). We recognize in him the same qualities we observe in Melville’s Ahab, or John Wayne’s Ethan Edwards in John Ford’s The Searchers: heroes pushed to extremis, forsaking simple sanity for the hunt. But Lu is less interested in the moral dimensions of those classics than he is in taking a more anthropological approach, casting a laconic gaze at these men in their life-threatening situations. Ga Yu is the ostensible guide through which we enter this world, but he all but disappears as those soaring camera shots and the close-ups of those native faces dominate. There is little melodrama or character development (save for Ritai or the youngster Liu Dong (Qi Yang), who reluctantly parts from his local sweetheart to take part in the mission) — instead, we bathe in action and aftermath. (Indeed, in interviews, Lu has revealed that many character-building moments were deleted from the final cut — a wise decision, given that they would only have intruded on the naturalism of the story.) In the film’s most harrowing scene, one of the patrolmen falls prey to quicksand, and the camera lingers on his empty jeep, the supplies he left by the side of the road, all of it rendered impotent by the swarming dust-storm winds, the parched landscape. It is in these furtive blasts of emotion that the film’s heart lies. The militiamen may not be defined, but there is no mistaking the compassion Lu has for them when they embrace each other in farewell, fully knowing that they may not survive.

|

Despite the bleakness of the narrative, Lu also finds moments of gallows humor. A militiaman chases a bandit on foot, but both of them are exhausted by the high altitude within seconds, their chase deteriorating into a staggering, drunken tango. A confrontation with illegal pelt peddlers turns into a bit of slapstick as the men strip to their long johns to pursue them across a river. Throughout, a Quixotic aura pervades the enterprise — Ritai is determined to “fine” and “arrest” the wrongdoers, but such bureaucratic language, and the militia’s dogged adherence to the “rules,” seems pitifully inadequate out in the wilds. Who would believe that a dozen men could track down a legion of bandits with their antiquated jeeps and popgun rifles? And yet, Ritai fulfills his quest in a fashion, and the awful consequences of that victory linger beyond those feel-good end titles. Bracing and fat-free, Kekexili portrays the clash between ambition and Mother Nature, and although it’s no surprise who wins, Lu’s economy slices through all rhetoric, political or otherwise.