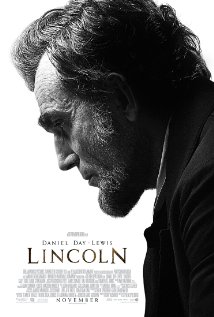

Lincoln (2012, Dir. Steven Spielberg):

Lincoln (2012, Dir. Steven Spielberg):

If it can be said that Steven Spielberg was fated to direct Schindler’s List, then it can also be said that he was meant to direct Lincoln. A picture about an underdog scrapping against the odds, the will to do the right thing, the optimism that is both the myth and engine that drives America — all of these things are right in Spielberg’s wheelhouse, and as one would expect, the film delivers all of the above, and surprisingly a bit more.

Spielberg has been down this road before, of course, from The Color Purple to Amistad, both of which concerned slavery and were standoffish in their dry, sanctified take on history. This time around the subject matter — Honest Abe’s last four months in office, where he was tasked with ending the Civil War and passing the contentious Thirteenth Amendment which legally freed the slaves — is, to be frank, juicier stuff, full of backroom (or more precisely, back-bar) dealings, political wheedling, compromise and skullduggery. Above all, it dovetails with Spielberg’s vision of our nation as a conglomerate of rabblerousing individualists, bickering, sometimes misguided, but impelled to be just and fair every so often. Coming in the midst of an election season in which the sentiment seems to be about the lesser of two evils, Lincoln underscores the mess that is the political process, and how glorious it can be when it actually works.

Presiding over it all is Lincoln himself, almost wraithlike, a shifting blur of calculation and cornpone, ready with a long-winded anecdote, an explosion of passion, a dab of melancholy, a rumpled integrity. In the hands of another lead actor, this would be all so theatrical — indeed, the screenplay by Tony Kushner can’t resist going showy at key moments, including an opening bit in which Lincoln is seated on a proscenium, a noble black Union soldier approaching to quote his Gettysburg address to him word for word (cue orchestral swell). Yet to their credit, Kushner and Spielberg sense that it would be somehow indecent to try to crack open the nut of this man, the nut that chroniclers have attempted to crack in a hundred different ways, and instead opt to give us an impression of him: the quicksilver moods, the inquisitive intelligence, the need to both engage and withdraw from those around him. Pointedly, by condensing most of its action to one month in Lincoln’s life, it serves as a summation rather than a full telling, thus avoiding the cliches of most biopics (the formative child years, the finding of the calling in life, etcetera).

Spielberg and Kushner are also fortunate that they have Daniel Day-Lewis to give breath to their creation. In addition to his near-perfect physiognomy, Day-Lewis is all about the stuff that broils within, and even as he tells a ribald joke about George Washington’s portrait in a Londoner’s water closet, or explicates Euclid’s first law as the ultimate example of the equality of man, one senses that there is always something held back, something hidden from everyone, including the man himself. (And just to prove he has an impish sense of humor, Spielberg throws in a reference to those “pettifogging Tammany Hall hucksters,” a tip of the cap to Scorcese’s Gangs of New York, which also featured Day-Lewis as a politician cut from a much different cloth). Unfurling his lanky body over tables, heavy of brow and surprisingly light of heart, Day-Lewis achieves the almost impossible goal of dominating every scene he is in without even appearing to try.

“I could write shorter sermons but once I get started I’m too lazy to stop.”

“I could write shorter sermons but once I get started I’m too lazy to stop.”

Lincoln is almost a chamber drama, with its long, unscored dialogue scenes in darkened rooms and rancorous courts of power, but for all of its dramatic import, Spielberg’s tone is more bemused than belabored. It’s not so much about the history lesson (although there is plenty of that, with historical visages and subtitles aplenty) as much as it is about capturing the churning momentum of those times, with grace notes of humor, mostly provided by the trio of “fixers” (a pot-bellied James Spader, John Hawkes, and Tim Blake Nelson) who must convince enough dissenting Democrats and fence-sitting Republicans to vote “yay” on the new amendment. The rest of the supporting cast both fall into type or work against it: David Straitharn is equally adept at chicanery and moral outrage as Secretary of State William Seward, while Sally Field, all needy and narcissistic and martyr-like, wears Mary Lincoln like an exquisitely corseted straitjacket. Best of all is Tommy Lee Jones, almost certainly assuring himself an Oscar, as he tamps it down as abolitionist and gadfly Thaddeus Stevens — apart from a scene in which he browbeats a fellow representative from Virginia and gets all, well, Tommy Lee Jones on him, he scores his points subtly, with a skeptical narrowing of the eyes, insults muttered under the breath.