Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008, Dir. Steven Spielberg):

Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008, Dir. Steven Spielberg):

It’s not the years honey, it’s the mileage.

So said Indiana Jones (Harrison Ford) back in 1981, in Raiders of the Lost Ark, and 27 years on, those words take on an additional poignance. Now it’s about the years and the mileage, as the 65-year old Ford and weathered filmmakers Steven Spielberg and George Lucas release the fourth chapter of the Jones saga. As Spielberg has said, there was never a pressing need to make this film—the third entry, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989), concluded with Indy and his fastidious father Henry Jones Sr. (Sean Connery) literally riding into the sunset. No, admitted Spielberg, this film wasn’t necessary, but it would be a valentine to the fans, a salute to their devotion to their hero over the years.

Raiders still towers over the genre as its own unique creation— unashamedly inspired by the pulp serials of Lucas and Spielberg’s youth, it upped the ante with A-class production values, a knowing sense of humor, and action sequences that were fleet-footed and bone-jarring. Raiders‘ lesser sequels Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984) and the Last Crusade tended to lean towards cartoonish bombast, but the die had been cast: these films set the template for action extravaganzas of the ’80s and ’90s, and their influence can be seen everywhere, from the increased action quota in the recent Bond films to the Da Vinci Code and the tongue-in-cheek “hunting for buried artifact” hijinks of Sahara and National Treasure.

Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull is a conscious throwback to those halcyon ’80s days, right down to the old-style Paramount logo that opens up the picture. Like the Bond series, Indy relies on familiar signposts—the beat-up fedora hat, the dusty booby-trapped tomb, Indy’s phobia of snakes, the scenes of old-style planes buzzing towards far-off destinations that are helpfully outlined on a map. This time around we’re in the year 1957, nearly 20 years after the last adventure: Indy is put on a trail that leads to a rumored lost city of gold in the heart of the Amazon when the young, well-coiffured Mutt Williams (Shia LeBouf) shows up on his university doorstep with a tale of a lost, mad professor (John Hurt) and a cadre of Soviet spies on his tail. This comes after a prologue in which Jones is kidnapped by the very same Russkies, escorted to Area 51, where all of this country’s secret artifacts are squirreled away (including the Ark of the Covenant, nudge nudge, wink wink), and asked to locate a magnetic coffin containing the skeleton of an alien (close encounters of the third kind, indeed). Leading the Commies is special agent Irina Spalko (Cate Blanchett), Stalin’s golden girl and a self-proclaimed psychic expert eager to claim the all-seeing knowledge of the aliens for Mother Russia. Working with Spalko (or against her, depending on whim) is Cockney mercenary Mac (Ray Winstone), whose money hunger knows no bounds.

Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull is a conscious throwback to those halcyon ’80s days, right down to the old-style Paramount logo that opens up the picture. Like the Bond series, Indy relies on familiar signposts—the beat-up fedora hat, the dusty booby-trapped tomb, Indy’s phobia of snakes, the scenes of old-style planes buzzing towards far-off destinations that are helpfully outlined on a map. This time around we’re in the year 1957, nearly 20 years after the last adventure: Indy is put on a trail that leads to a rumored lost city of gold in the heart of the Amazon when the young, well-coiffured Mutt Williams (Shia LeBouf) shows up on his university doorstep with a tale of a lost, mad professor (John Hurt) and a cadre of Soviet spies on his tail. This comes after a prologue in which Jones is kidnapped by the very same Russkies, escorted to Area 51, where all of this country’s secret artifacts are squirreled away (including the Ark of the Covenant, nudge nudge, wink wink), and asked to locate a magnetic coffin containing the skeleton of an alien (close encounters of the third kind, indeed). Leading the Commies is special agent Irina Spalko (Cate Blanchett), Stalin’s golden girl and a self-proclaimed psychic expert eager to claim the all-seeing knowledge of the aliens for Mother Russia. Working with Spalko (or against her, depending on whim) is Cockney mercenary Mac (Ray Winstone), whose money hunger knows no bounds.

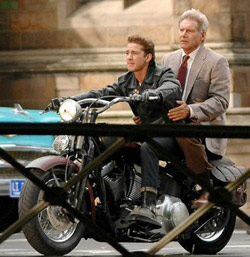

Naturally, not all is as it seems, and plenty of twists and turns crop up before Indy and friends arrive at the fabled city. It’s no big secret that Mutt is the lad Indy sired with Marion Ravenwood (Karen Allen), the feisty heroine of Raiders, and most of the fun of the movie’s first half comes from Indy and Mutt’s guarded interactions. Indy is bemused at the younger man’s incredulousness at his exploits; Mutt has a chip on his shoulder and a way with a switchblade, when he’s not making like Marlon Brando on the back of his motorbike and saving Indy’s skin during a fun chase across Yale University’s grounds. Soon we’re off to the Nazca lines in Peru, and then to the heart of the South American jungle, where the principals take turns betraying each other and stealing the titular crystal skull, which holds the key to the lost city.

Naturally, not all is as it seems, and plenty of twists and turns crop up before Indy and friends arrive at the fabled city. It’s no big secret that Mutt is the lad Indy sired with Marion Ravenwood (Karen Allen), the feisty heroine of Raiders, and most of the fun of the movie’s first half comes from Indy and Mutt’s guarded interactions. Indy is bemused at the younger man’s incredulousness at his exploits; Mutt has a chip on his shoulder and a way with a switchblade, when he’s not making like Marlon Brando on the back of his motorbike and saving Indy’s skin during a fun chase across Yale University’s grounds. Soon we’re off to the Nazca lines in Peru, and then to the heart of the South American jungle, where the principals take turns betraying each other and stealing the titular crystal skull, which holds the key to the lost city.

For a while Kingdom of the Crystal Skull is genial entertainment, preferring to lay back and lay on the exposition while a few nifty action sequences add pep. Certainly it approximates the look and feel of your standard lavish Indy adventure, as cinematographer Janusz Kaminski deliberately echoes the great Douglas Slocombe’s rich palette from the ’80s films. The movie’s major setpiece, a motorcade chase in the jungle in which the antagonists find themselves playing musical jeeps, has a sprightly momentum when it’s not cutting away to the sight of Mutt making like Tarzan with a multitude of CGI monkeys.

Yes, CGI—before too long it becomes apparent that Kingdom is crammed wall-to-wall with it, from imagined exotic locales to computer-generated groundhogs and killer ants, and a finale featuring a collapsing city that might as well be a bunch of floating pixels. The earlier Indy adventures didn’t shy away from effects, or even dodgy ones, but the settings and practical stunts maintained an earthbound quality to them; here, your eyes are apt to glaze over when you see two combatants clash swords as they stand on separate jeeps zooming at 60 miles per hour in a green-screened jungle. The concept is fine in theory, but the artificiality of the effects dulls out the edge.

Yes, CGI—before too long it becomes apparent that Kingdom is crammed wall-to-wall with it, from imagined exotic locales to computer-generated groundhogs and killer ants, and a finale featuring a collapsing city that might as well be a bunch of floating pixels. The earlier Indy adventures didn’t shy away from effects, or even dodgy ones, but the settings and practical stunts maintained an earthbound quality to them; here, your eyes are apt to glaze over when you see two combatants clash swords as they stand on separate jeeps zooming at 60 miles per hour in a green-screened jungle. The concept is fine in theory, but the artificiality of the effects dulls out the edge.

While Spielberg’s reflexes as an action filmmaker are still very much present, these movies require more than muscle memory; they depend on zip, economy, and a devil-may-care brio. Tons of things are explained in Kingdom, plenty of confrontations occur, and John Williams throws in familiar musical motifs in an effort to get the blood flowing, and yet the movie lacks urgency or an overriding reason to care. In outline, the story is a Spielbergian meditation about family, as Indy, Marion and Mutt form reluctant domestic ties, but their repartee is minimized by the constant exposition, as mumbo-jumbo over clues and locations pile up. Spielberg in his salad days would no doubt push pedal to the metal in order to get to the good stuff, and he might have had the room to do so if it wasn’t for Lucas (who came up with the basic story with Jeff Nathanson). It’s clear the Star Wars überlord hasn’t shaken off the over-talkiness that plagued that franchise’s prequels, and the result is a protracted, distracted plot. Marion and Indy may trade a few zingers, yet their rekindled love receives a grand total of about 30 seconds on screen, while Indy and Mutt’s easy chemistry tends to get lost amid the dusty caverns, trap doors and collapsing structures that occupy every inch of the frame during the story’s final act.

While Spielberg’s reflexes as an action filmmaker are still very much present, these movies require more than muscle memory; they depend on zip, economy, and a devil-may-care brio. Tons of things are explained in Kingdom, plenty of confrontations occur, and John Williams throws in familiar musical motifs in an effort to get the blood flowing, and yet the movie lacks urgency or an overriding reason to care. In outline, the story is a Spielbergian meditation about family, as Indy, Marion and Mutt form reluctant domestic ties, but their repartee is minimized by the constant exposition, as mumbo-jumbo over clues and locations pile up. Spielberg in his salad days would no doubt push pedal to the metal in order to get to the good stuff, and he might have had the room to do so if it wasn’t for Lucas (who came up with the basic story with Jeff Nathanson). It’s clear the Star Wars überlord hasn’t shaken off the over-talkiness that plagued that franchise’s prequels, and the result is a protracted, distracted plot. Marion and Indy may trade a few zingers, yet their rekindled love receives a grand total of about 30 seconds on screen, while Indy and Mutt’s easy chemistry tends to get lost amid the dusty caverns, trap doors and collapsing structures that occupy every inch of the frame during the story’s final act.

The actors do what they can with their lackluster material. Dressed in fatigues that would seem more suited for a plane mechanic, her face jutting out from beneath a black bob cut, Blanchett is cartoonish yet alluring as Spalko; it’s a shame her character isn’t allowed to develop into a true threat. Old pros Hurt and Winstone don’t even have a chance to make an impression, as they’re basically relegated to the scenery. To his credit, Ford slips into the role of Indy like a weather-beaten pair of slippers, and for a 65-year old he shows admirable energy and physical grace. Still, his performance has a touch of dullness to it, as if he (like Spielberg and Lucas) is shaking off the cobwebs even as he tries to pull the old moves.

For all its subplots and hinted-at themes (how to age gracefully, the corrupting pursuit of knowledge for power), Kingdom lacks the unity of the previous Jones adventures, hoary as they sometimes were. Raiders concluded that some things are not meant to be known, even as it celebrated the derring-do that goes into the quest. The darker Temple of Doom was a parable about Bogart-like nobility in the face of despicable subjugation, while the more humanist Last Crusade suggested that family bonds are way more important than archaeological glory or even immortality. Spielberg has always been push-pull when it comes to conservative values and adventure: new-fangled gadgetry and obsessive quests are always butting heads with home, hearth, and old-fashioned American middle-class life, neither quite able to exist without the other. But in Kingdom, domesticity wins the battle, whether that domestic setting is a staid university classroom or a final wedding inside a blindingly white church. Setting aside that sweet conclusion (and a final sly shot of Mutt—or should we say Henry Jones III—holding Indy’s fabled fedora in his hands, a faraway look in his eyes), you’ll find little in the rest of the movie that’s actually transporting. If Raiders is a race car ride through the desert, sand and wind flying in your face, then Kingdom is a meandering bus tour complete with jokey tour guide: you may look fondly upon the land as it passes by, note spots which seem mighty familiar, and remember when it was all fresh and new, when we all had a little less mileage on us. ■

For all its subplots and hinted-at themes (how to age gracefully, the corrupting pursuit of knowledge for power), Kingdom lacks the unity of the previous Jones adventures, hoary as they sometimes were. Raiders concluded that some things are not meant to be known, even as it celebrated the derring-do that goes into the quest. The darker Temple of Doom was a parable about Bogart-like nobility in the face of despicable subjugation, while the more humanist Last Crusade suggested that family bonds are way more important than archaeological glory or even immortality. Spielberg has always been push-pull when it comes to conservative values and adventure: new-fangled gadgetry and obsessive quests are always butting heads with home, hearth, and old-fashioned American middle-class life, neither quite able to exist without the other. But in Kingdom, domesticity wins the battle, whether that domestic setting is a staid university classroom or a final wedding inside a blindingly white church. Setting aside that sweet conclusion (and a final sly shot of Mutt—or should we say Henry Jones III—holding Indy’s fabled fedora in his hands, a faraway look in his eyes), you’ll find little in the rest of the movie that’s actually transporting. If Raiders is a race car ride through the desert, sand and wind flying in your face, then Kingdom is a meandering bus tour complete with jokey tour guide: you may look fondly upon the land as it passes by, note spots which seem mighty familiar, and remember when it was all fresh and new, when we all had a little less mileage on us. ■